|

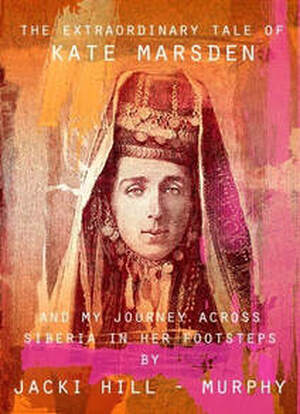

This is a story that defies all reason: a Victorian spinster and nurse, so obsessed with the fate of leprosy-sufferers worldwide that she was prepared to journey, in winter, nearly ten thousand miles across pre-revolutionary Russia, to one of the most inhospitable areas on earth, first to find a legendary plant that might be a cure, and report on living conditions of sufferers in the remote Siberian forests.

I went to walk her steps... |

|

In Yakutsk Jacki gave a speech at the Council of Europe Seminar “The European Social Charter – on the way to human rights’. She inspired delegates from across the globe on the extreme humanitarian work of Kate Marsden. This Victorian British nurse, whose journey across Russia to Vilyuisk is probably the toughest journey ever undertaken by a woman, is loved and respected there due to her work in the forest on behalf of lepers. Jacki’s speech centred on the practical humanity of Kate Marsden and how her selfless work inspires the work of social workers and carers in all regions of the vast Sakha Republic.

Present at the forum were the Deputy Prime-Minister of the Republic of Sakha (Yakutia), the President of the Russian Union of Social Workers, the Minister of Labour and Social development of the Republic of Sakha, the director of Directorate of the European Social Charter of the Council of Europe and many more. |

VilyuiskAt the nearby town of Viyuisk Jacki enjoyed many opportunities to interact with the local community who were keen to show their love and respect for Kate Marsden. Jacki received awards from the mayor and college principal for her work with the town and she made a presentation to the museum of a signed first edition of Kate’s book. Kleopatra, the doctor in charge of the hospital that now stands on the site of the original hospital, can be seen receiving it in this photograph.

|

White Nights in the Dark Forest

|

Twenty four hours of daylight can play havoc with your body clock, particularly one that is already jet lagged from crossing numerous Siberian time zones en route from the UK. I closed my eyes and willed myself to sleep while a searchlight of sun shone into my face through a gossamer-thin curtain.

It would be a week before I saw the sun set again. A white night in June never gets dark at high latitudes and Yakutsk in Sakha Province is located about 450 kilometers south of the Arctic Circle. Yakutsk is a city of many extremes; it is the coldest city on earth built alongside the River Lena. The permafrost ground creates an architect’s head ache and concrete piles hold up the buildings which are laced with crudely lagged waste and water pipes that can’t be dug under the ground. If it’s not enough for the Yakuts to scuttle around for eight months with temperatures as low as -60°C, they also do that in the dark, as December daylight is from 11.00 am till 3.30 pm. As I tried to sleep in the night sunshine I wondered whether Yakuts people, deprived of sun and light for so much of the year sunbathed at midnight to compensate. I’d seen them with shopping bags on the ride from the airport at 3am and I marvelled at the human’s ability to adapt to such difficult surroundings. |

I love these people and when my clock told me it was morning I sprang out of bed in that bright room, ready to head off on a 600 kilometre car journey through the forest, that’s the equivalent of driving from Brighton to Edinburgh in Great Britain, on an unmade road for my second visit to Vilyuisk. Look at a map and you are reminded that an ocean of wild, inhospitable forest surrounds Yakutsk that is as big as America and driving through it is endless. Vilyuisk is a mere pin prick. It’s an island village of 12,000 people in this ocean of trees whose lives are geared to the rhythm of nature and the seasons. They are the woodlanders and the horse breeders who now boast a successful teacher training college. They lead cultured and respectable lives in their wooden houses, driving their cars over mud tracks and there are women’s groups who sew beautiful flowery long dresses who look forward to a guest visiting their town to dress up and sing for…

Remarkably, I was the first visitor since I came two years earlier. I was in for a treat. The town had been preparing for my visit and I was about to receive the full Vilyuisk treatment … This entry was posted in Expeditions on June 29, 2015 by pinkginger. |

The Lonely Grave - A Lonely London Grave gets some Siberian Love

by Jacki Hill-Murphy

by Jacki Hill-Murphy

|

On the 82nd Anniversary of the Victorian nurse and explorer Kate Marsdenʼs death, her unmarked and overgrown grave has been found and an interesting ceremony has taken place to mark her life…

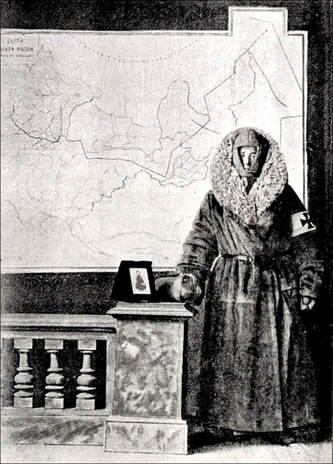

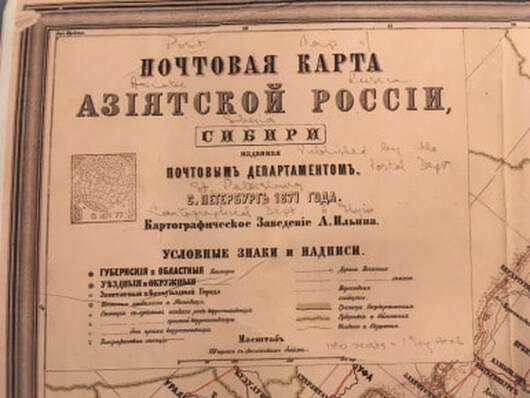

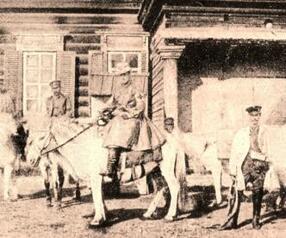

Tucked away on the far edge of Hillingdon cemetery near Uxbridge, an unmarked grave has laid, unvisited, for over 80 years – until 2014. It lies beneath a canopy of straggly May blossom and beside the plastic detritus of a hedge bordering a housing estate and sinking Victorian graves that look like they have been washed up in a storm. This is the final resting place of Kate Marsden (1859 – 1931) to some a hero, tough experienced nurse, fund raiser, who had made a remarkable journey across Siberia in 1891 and established the first leper colony in Russia. To others though she was a fraudster, a deceiver and totally immoral and she was hounded unmercifully until she died, penniless and alone, in a Wandsworth mental institution at 72. Undaunted by the criticism made against her I set off last summer to recreate 4,000 miles of her grueling journey, which she undertook in 1891 by sledge, cart, cargo ship and on horseback, across Siberia, most of it in sub-zero conditions. Kate had become obsessed with the idea that she could mastermind some sort of cure or relief for the lepers she had been encountering whilst nursing the wounded men of the war between Russia and Turkey in 1878 and was told there was a herb in Eastern Siberia that may do that; it seemed to have been the purpose she was looking for in her life. She left after seeking out imperial assistance from Englandʼs Queen Victoria and Maria Feodorovna, Empress of Russia. The journey for her was horrendous and documented in her book ʻOn Sledge and Horseback to Outcast Siberian Lepersʼ, although frustratingly for me, trying to revisit it, there are huge chunks of the journey that she doesnʼt comment on, for example, over 2,000 miles on a crude, insect infested cargo boat on the great River Lena which only receives a paragraphʼs mention. These omissions, plus a title more synonymous with a Gothic horror novel, became a portal in which skepticism would be fostered in an era where women were not applauded for any fantastically dangerous and courageous adventure. While in Russia her focus shifted when she heard about the horrific conditions under which Russian lepers were forced to live and she set off from Yakutsk, on horseback, on a two thousand mile journey to visit lepers in the forests around Vilyuisk to gather information and see for herself the terrible conditions in which they were forced to live. By doing this she inadvertently completed one of the most difficult equestrian journeys of the late 19th century. The money she raised afterwards built a leper colony for these wretched people. I can vouch that she made that journey. The final leg of my overland journey to follow in her footsteps in August 2013 was a 20 hour, 400 mile, minibus journey on unmade roads through the Siberian forest from Yakutsk to Vilyuisk. After meeting the Mayor I was taken to Sosnovka, eight miles away, where the leper colony was built, |

which opened in December 1892 and carried on its great work through the Bolshevik revolution and the civil war before closing in the 1960s.

There is now a hospital for dementia patients on the site adjacent to the remains of the collapsing wooden leprasorium. The raptuous welcome from the villagers of Sosnovka completely took me by surprise, they had come out to greet me in costumes representing the history and tradition of the region, including many in nurseʼs uniforms dating back to the 1890s; there was even a Kate Marsden herself in her little grey suit and hat. The Director of the hospital, Kleopatra, proudly showed me and my travelling companion Rebecca, who was incidentally the first Australian to ever visit Vilyuisk and Sosnovka, the little museum dedicated to Kate Marsden and this costumed community followed us in a throng on a guided tour of the site. It is not possible to feel more love for a deceased person than those people showed for Kate Marsden, after a succession of Siberian tea parties and mareʼs-milk sipping ceremonies, where I had a horse-hair switch swished around me and speeches were made I was led to an empty plinth on a patch of grass. Kleopatra told me that this was waiting for Kateʼs statue; perhaps soon they would have the funds to erect one. Kate Marsden never returned to see her hospital built with the funds that she raised; she never returned to Siberia. She became one of the first women to be elected a Fellow of the Royal Geographical Society and founded the St. Francis Leprosy Guild in London but scandal continued to dog her for the rest of her life and there were campaigns to discredit her in England, Russia and New Zealand. Charges against her included embezzlement of the funds that sheʼd raised to build the hospital, deception by orchestrating falling out of a linen cupboard in a hospital in Wellington in New Zealand, where she was a matron, shortly after buying two life insurance policies. However, most unforgivable were the allegations of lesbianism, this at a time when Oscar Wilde was on trial. They may have been unproved but they were enough to destroy her reputation. On that Saturday in March a motley crew of singing and harp-playing Siberians and British devotees gathered around the sad sight of Miss Marsdenʼs grave, barely visible beneath its blanket of brambles and weeds in a West London Cemetery. It had been found by the present day Kate Marsden, an indomitable figure to the Victorian Kate Marsdenʼs cause. Elena Kychkina, the sister of my translator in Vilyuisk happened to be in London and she also happened to have Kuprian Mikhailov an actor of the Sakha National Drama Theatre with her who just happened to have had a dream to bring his shamanʼs outfit with him and they hung their rag streamers, read out a eulogy, gave Russian pancake offerings, the shaman beat his drum and shook his long hair and we laid our offerings on the newly cleared grave. They told me afterwards, ʻthere was some mystic in the air as though the ceremony was being guided by bright powersʼ. Kate Marsden would have loved it. This entry was posted in Expeditions on November 23, 2013 by pinkginger. |