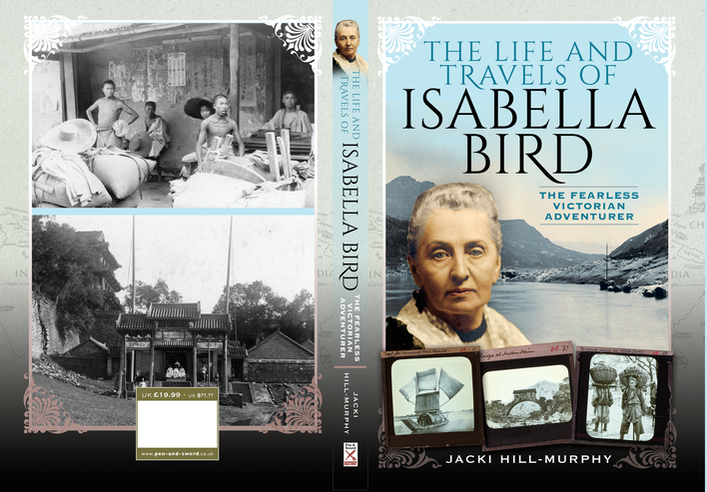

Jacki's new book will be published in Febuary 2021 by Pen & Sword. Please revisit for a link to purchase

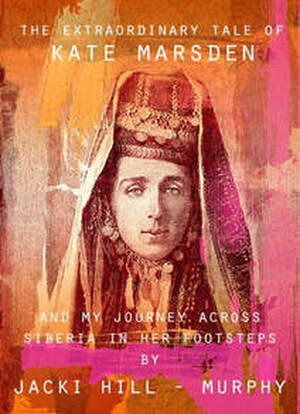

The Extraordinary Life of Kate Marsden

This is a story that defies all reason: a Victorian spinster and nurse, so obsessed with the fate of leprosy-sufferers worldwide that she was prepared to journey, in winter, nearly ten thousand miles across pre-revolutionary Russia, to one of the most inhospitable areas on earth, first to find a legendary plant that might be a cure, and report on living conditions of sufferers in the remote Siberian forests.

Sadly, her ambitious plans and fund-raising were thwarted by jealous detractors, who scandalised her worldwide. Jacki travelled across Siberia to see for herself the truth of her journey and found a remote village in the forest still celebrating her over a hundred years later.

Throughout the book Jacki goes back in time to talk to her in a variety of relevant Victorian venues, in an attempt to unravel the truth.

A cracking yarn in the Siberian footsteps of a Victorian heroine who defied homophobia to fight leprosy. Read it.

- John Sweeney, Author and Broadcaster

‘Jacki’s book is a literal first and a manuscript prepared by a true explorer, searching for the truth about an extraordinarily courageous women, who devoted her life to those less fortunate. I commend this book in every sense, a Siberian tale that unfolds into a mosaic of courage and commitment, in one of the coldest places on earth’.

- Ken Hames MBE, Adventurer and Presenter

‘A monumental, spellbinding book full of beautiful prose and wild exploration which is likely to become a classic and new genre in adventure writing.’

- Tor Torkildson, Editor, The Walkabout Chronicles: Epic Journeys by Foot

Sadly, her ambitious plans and fund-raising were thwarted by jealous detractors, who scandalised her worldwide. Jacki travelled across Siberia to see for herself the truth of her journey and found a remote village in the forest still celebrating her over a hundred years later.

Throughout the book Jacki goes back in time to talk to her in a variety of relevant Victorian venues, in an attempt to unravel the truth.

A cracking yarn in the Siberian footsteps of a Victorian heroine who defied homophobia to fight leprosy. Read it.

- John Sweeney, Author and Broadcaster

‘Jacki’s book is a literal first and a manuscript prepared by a true explorer, searching for the truth about an extraordinarily courageous women, who devoted her life to those less fortunate. I commend this book in every sense, a Siberian tale that unfolds into a mosaic of courage and commitment, in one of the coldest places on earth’.

- Ken Hames MBE, Adventurer and Presenter

‘A monumental, spellbinding book full of beautiful prose and wild exploration which is likely to become a classic and new genre in adventure writing.’

- Tor Torkildson, Editor, The Walkabout Chronicles: Epic Journeys by Foot

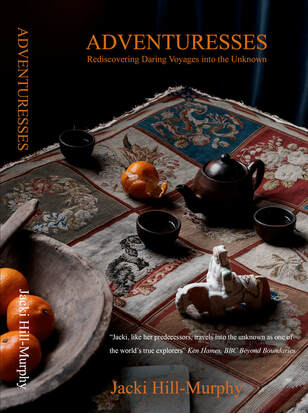

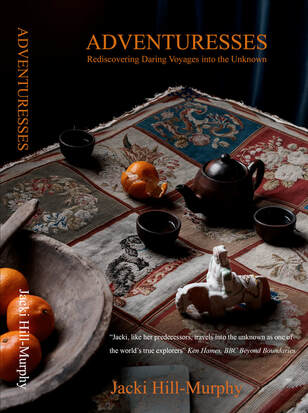

Adventuresses, Rediscovering Daring Voyages into the Unknown

"...delightful stories of travel obscurities and surprises that only a genuine explorer can communicate as she seems to remember every tiny detail from all her senses and has a way of describing people that is heart warming and memorable.” - Daniel Jones ITV/BBC Producer/Director

Extracts from the book…

“Once again I tried to put myself in Isabela’s embroidered slippers, and imagine her mixture of abject discomfort and apprehensiveness at every unfamiliar sound or movement of the alien forest, from the sudden fall of a tree to the cry of the bellbird and the bark of the howler monkey. Pinch yourself Jacki, in the sealed safety of your dry cab; at least you have the assurance of arrival at the end of the ride! I noticed my team mates had gone a bit quiet and guessed that Mary in particular was pondering the recklessness of the expedition leader in transferring us all to the Bobonaza, in a dugout canoe of all things, in weather like this. “

“A further disincentive to rising and shining was the clear realisation that this probably wasn’t a good day for going anywhere. It might, though, be just the day for Plan B. Slowly we coaxed our way into camp life: a lick and a promise with wet wipes, dry socks, a shake out of the boots, and secret rummages into the depths of our packs for a reserved treat – a granola bar, perhaps. I looked out under the dripping eaves of the corrugated roof, where our wet trousers hung limply, hoping to catch a sunray if it popped its head out from the white misty sky, and there, on the edge of the concrete deck, stood my brave Angela applying full West End makeup.

The yellowy green and brown hummocks spread out around us and we could see a distant incline which, from Mary Kingsley’s description, I could now point out to my team as announcing the start of the main peak. That, of course, now lost in a cloud. It was a mossy, drippy, dank and miserable world – but I had my plan to brighten it up.

The time had come to pull out those long frocks. One condition of joining the expedition was to bring a late Victorian outfit, in Mary’s honour. Each of us therefore, somewhere rolled tight into a plastic bag in a corner of our damp luggage, had an outfit that Mary would not have scorned.”

“While Isabella was picking her way across the ‘impassable barrier’ of the Khardung La I was walking back along a parallel one – the Lasirmou La passing through the tiny isolated hamlets of Wachan, Yogma, Dok, Brok, and Yanok. Travelling by a vehicle along a motor road back to Leh had never been my plan and I didn’t see much pleasure in walking for a hundred miles along tarmac, instead I was heading into a fabulously remote, unvisited part of the Ladakh Mountain range, a landscape Isabella would have loved. I wanted to walk, I wanted time to think, I wanted to be with the ponies and the Tibetan cooks and the lovely guide for longer, and I wanted more time to consider the differences in the lives of the Victorian lady and myself on our walks through the Himalayas.

My own party left at 9am under a clear blue sky and we trekked for three hours through a canyon, past stone mantras with beautiful carved Sanskrit prayers which were framed by the brown gravelly mountains of the Ladakh mountains and far beyond them the snow capped Zaskar massif. Bare larch boughs, bent with the weight of streamers of prayer flags, fluttered in the breeze; on dainty log-bridges we crossed full rushing rivers of blue water and followed neglected, half-collapsed stone walls and the first attempts at a cleared track.”

“Once again I tried to put myself in Isabela’s embroidered slippers, and imagine her mixture of abject discomfort and apprehensiveness at every unfamiliar sound or movement of the alien forest, from the sudden fall of a tree to the cry of the bellbird and the bark of the howler monkey. Pinch yourself Jacki, in the sealed safety of your dry cab; at least you have the assurance of arrival at the end of the ride! I noticed my team mates had gone a bit quiet and guessed that Mary in particular was pondering the recklessness of the expedition leader in transferring us all to the Bobonaza, in a dugout canoe of all things, in weather like this. “

“A further disincentive to rising and shining was the clear realisation that this probably wasn’t a good day for going anywhere. It might, though, be just the day for Plan B. Slowly we coaxed our way into camp life: a lick and a promise with wet wipes, dry socks, a shake out of the boots, and secret rummages into the depths of our packs for a reserved treat – a granola bar, perhaps. I looked out under the dripping eaves of the corrugated roof, where our wet trousers hung limply, hoping to catch a sunray if it popped its head out from the white misty sky, and there, on the edge of the concrete deck, stood my brave Angela applying full West End makeup.

The yellowy green and brown hummocks spread out around us and we could see a distant incline which, from Mary Kingsley’s description, I could now point out to my team as announcing the start of the main peak. That, of course, now lost in a cloud. It was a mossy, drippy, dank and miserable world – but I had my plan to brighten it up.

The time had come to pull out those long frocks. One condition of joining the expedition was to bring a late Victorian outfit, in Mary’s honour. Each of us therefore, somewhere rolled tight into a plastic bag in a corner of our damp luggage, had an outfit that Mary would not have scorned.”

“While Isabella was picking her way across the ‘impassable barrier’ of the Khardung La I was walking back along a parallel one – the Lasirmou La passing through the tiny isolated hamlets of Wachan, Yogma, Dok, Brok, and Yanok. Travelling by a vehicle along a motor road back to Leh had never been my plan and I didn’t see much pleasure in walking for a hundred miles along tarmac, instead I was heading into a fabulously remote, unvisited part of the Ladakh Mountain range, a landscape Isabella would have loved. I wanted to walk, I wanted time to think, I wanted to be with the ponies and the Tibetan cooks and the lovely guide for longer, and I wanted more time to consider the differences in the lives of the Victorian lady and myself on our walks through the Himalayas.

My own party left at 9am under a clear blue sky and we trekked for three hours through a canyon, past stone mantras with beautiful carved Sanskrit prayers which were framed by the brown gravelly mountains of the Ladakh mountains and far beyond them the snow capped Zaskar massif. Bare larch boughs, bent with the weight of streamers of prayer flags, fluttered in the breeze; on dainty log-bridges we crossed full rushing rivers of blue water and followed neglected, half-collapsed stone walls and the first attempts at a cleared track.”