The Treasure of the Llanganates refers to a huge amount of gold and silver supposedly hidden deep within the Llanganates mountain range of Ecuador by the Inca general Rumiñahui.

In 1532 Francisco Pizarro captured the Inca king Atahualpa at Cajamarca. Atahualpa, seeing that the Spaniards cherished gold above all, promised to fill a room with gold and another equally large with silver in exchange for his freedom.

Pizarro agreed to do this, although he likely had no intention to ever let Atahualpa leave. Before the room could be filled with gold, Pizarro killed the Inca king.

The legend holds that the Inca general Rumiñahui was on his way to Cajamarca with an enormous amount of worked gold for the ransom when he learned that Atahualpa had been murdered and the porters diverted into the Llanganates and hid them.

In 1532 Francisco Pizarro captured the Inca king Atahualpa at Cajamarca. Atahualpa, seeing that the Spaniards cherished gold above all, promised to fill a room with gold and another equally large with silver in exchange for his freedom.

Pizarro agreed to do this, although he likely had no intention to ever let Atahualpa leave. Before the room could be filled with gold, Pizarro killed the Inca king.

The legend holds that the Inca general Rumiñahui was on his way to Cajamarca with an enormous amount of worked gold for the ransom when he learned that Atahualpa had been murdered and the porters diverted into the Llanganates and hid them.

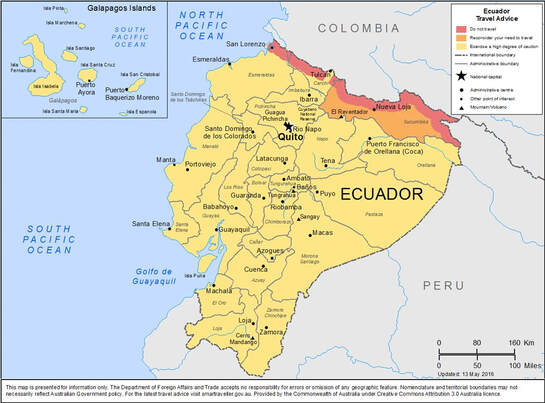

A map with a trail that was set 500 years ago, wild terrain where compass needles whiz round uncontrollably, spectacled bears sniffing around the tent at night, tapirs scuttling around in the bush and thick black squishy mud as far as the eye can see! Yes this is the Llanganates in the Andes of Ecuador, where literally, no one ever goes. So why am I going there with my team of three intrepid and enthusiastic ladies into this wild, wet and unexplored quagmire, a water-world in a vast and far-off land?

We are going to bring back our stories and share them, of being in a mysterious wonderland of nature, recording and documenting it, like the first female explorers did of distant lands whose stories were read by those who could only dream of such a journey.

As for Isabela, we will pay our respects by her lake and commiserate with her, for the total lack of planning and equipment by her husband Colonel Brookes in his attempt to find Inca Gold there in the 1920s.

As for Isabela, we will pay our respects by her lake and commiserate with her, for the total lack of planning and equipment by her husband Colonel Brookes in his attempt to find Inca Gold there in the 1920s.

Female Footsteps in the Wild Llanganates

This could have been a foolhardy expedition, people have died over the years in this remote and wild region of the Ecuardorian Andes but we stayed safe and succeeded in our mission, which was to follow the dotted line on an old map which denoted an ancient Inca Trail. The trail apparently leads to a hoard of Inca gold – the ransom for the Inca King Atahualpa, hidden and not delivered to the Spanish Conquistadores who kidnapped the king. I wanted us to reach the part of the map where the dots ran out…

|

Isabela Brookes may have been coerced or bullied into going there with her new husband, Colonel Edward Brookes, a mad keen treasure seeker in 1920 for their honey-moon. We don’t have a photograph of the unfortunate lady but her story is fascinating and she trudged through the mud with a reluctant band of local men to show them the way into the heart of the park in search of Inca Gold. Was she wearing a long skirt I wonder, or had this local lady from the Andes succumbed to the new-fangled ‘trousers’ that were now almost acceptable clothing for a lady and would have added some sarto-rial comfort for her.

The Colonel had one thing on his mind – Gold, as they trekked closer to towards the Cerra Hermosa in the heart of the wilderness he may have begun to regret his lack of organisation in seeking out the fabled hoard as Isabel stumbled along behind him. She was hoping that the sun would shine and dry her out and that the sharp cold winds would give way to a gentle breeze – but is wasn’t to be and she succumbed to pneumonia. After a couple of days she sadly died, probably caught from getting thoroughly soaked in her tent. The men they had paid to go with them got scared and ran away and Colonel Brookes had to find his own way out, now a widower. |

Or was he? Legend has it that he already had a wife in America.

There are orchids galore in this area of outstanding nature, many don’t have names yet and little gardens of succulent plants cling to rocks in picturesque clusters. Bright blue and orange birds fly close, quite unafraid of humans, who they have never seen.One of the lakes that emerges form the mist is called Isabela Brookes Lake, it is small and the shallow water surface ripples and long grasses skirting it toss in the wind. Another is shaped like a heart, a cruel twist in Isabela’s story. The terrain is rugged and mountainous but cloud forest grows thickly on the slopes, valleys seem to lead nowhere and just when you has finished smoothing sunblock onto your face, the hot sun will give way to snow, or hail or the wind will blow up a storm. Off come the layers of clothing and on they go again, hoods up and hoods down, peel off the wet waterproof trousers and then back down to a t shirt. It is a mad world for weather, a mad world for testing your survival skills but a fantastic world for beauty in nature in the landscapes, for testing yourself against the elements when you are a mere speck in an unspoilt world that has never seen a combustion engine. The team, Becky Condron, Patricia Tyler, Jo Costello and myself, left in November 2018 and all of us were fired up to penetrate this notoriously difficult region on the Andes. We were well equipped with waterproof coats and shirts from Craghoppers and all wore knee high wellington boots, wearing them turned out to be a good decision. Flying into Quito at almost 3000m above sea level can be challenging for those who suffer altitude sickness and we took it slowly knowing we would be reaching nearly 4,500m on the expedition. As preparation is the key to success on an expedition into such a wild place we had guides and porters who knew the area waiting for us in Pillaro, without these man we would have died. The three killers are pneumonia, which Isabela Brookes died from after three days of being in the park, in 1920, while treasure seeking with her husband Colonel Brookes; infected cuts from the sharp vegetation like razor grass and getting lost. Tripping over one of the many roots growing under the mud and impaling yourself on a broken tree trunk or breaking a limb were also a worry to me as the team leader.

|

|

Everyday we faced our fears in this tough terrain, each step we took was challenging and had the level of difficulty of an SAS training ground, of which part of the Llanganates is used for. We left the open plains or paramo dotted by lakes fairly early on and plunged into cloud and lowland deciduous forest which our local guides hacked through with their machetes. Without these men we could now have contemplated this journey and as the days went by we became a family; sharing the intense discomforts and laughing together. They carried heavy bags but each seemed to bound along effortlessly, they were so nimble and fit. Two porters were Venezuelan refugees who had walked to Ecuador with only the clothes they stood up in, which took them 15 days. The other three were Shuar Indians who had been displaced from Moreno Santiago district by the army with tanks to allow the oil drillers to take over their land. One of our guides was a lovely little man of 80 who first went into the Llanganates at 12 and had led many early early gold seekers.

|

|

Our GPS stopped working for a few days as a signal couldn’t be found in the dense forests. This caused a flurry of excitement with the family and friends tracking us and the schoolchildren who has signed up to following our expedition with Noah’s Ark Zoo in Wraxall in Bristol. One of the main interests for them was that we we would be trekking through the natural homeland of the animals in the South American enclosure, these are principally Andean or spectacled bears, tapirs, capybaras. This is also the land of pumas and the majestic large winged condor. Each day I discussed the route with our guides using the Derretero and the old map and we drew each campsite onto it and compared it to the military map.

|

When the mist lifted, or the rain stopped, or if we broke through a clearing in the dense cloud or lowland forest and glimpsed the extraordinary and mysterious landscape around us we felt the sense of being somewhere special and inhospitable, so much so that not even the Incas were able to settle there to escape the Spanish invaders. At night we heard the tapirs as they came into camp but they sensed our presence and we never saw any, I did see a capybara and many eagles and birds. We saw the tracks and evidence of the Andean bear, wolves and puma. The tapir ticks prayed on us though and we all had to remove them from our backs.

|

|

The biggest problem was the deep mud, quaking bogs, swarms of mosquitoes when we stopped and stopping the unfriendly sharp branches from hitting us, I acquired a black eye from a particularly viscous fern. The razor grass sliced our hands when we fell and every step had an obstacle trying to trip us up or pull us in. We had to clamber over logs, haul ourselves over boulders, drag ourselves up muddy hills on our hands and knees and slither through small spaces and across rivers; I am so glad that we escaped without serious injury. For ten days we were specks in an unknown wilderness and we showed, without doubt, that neither age or gender can prevent someone going above and beyond and in our case, being the first women to do so. I have the document to prove that!

|

Camping was challenging as the rain pelted down on us every night and the soft mud made guy ropes hard to keep in, we always managed to clamber into a dry sleeping bag at night and our morale was always high and we were a good team, helping each other out and laughing in the face of adversity. It was hard, memorable and a very big adventure. To quote a guide, “I have seen grown men weep on their first day in this place”.

I would like to thank my main sponsor profusely and also Craghoppers for the clothing that protected us so well and for everyone’s kindness and interest in the expedition and to Becky, Patricia and Jo for making it through. |