|

|

Expedition to Travel the Length of the Amazon River

by Jacki Hill-Murphy, Instigator and bashful leader.

by Jacki Hill-Murphy, Instigator and bashful leader.

|

September 5th 2016

One month to go and I feel like I am on a countdown. Each morning I wake up and check my list for the day – and add to it with my night-time jungle wanderings. The e mails that need responding to are relentless; a bit like the river I will be descending along. The appeal of this 4,200 miles of dark, muddy water is its mystery, we are brave enough to enter this unknown world, but a very large proportion of the population wouldn’t want to go near it. It’s like asking them to become a fictional creation like Poirot – why would you want to investigate a murder? Or to sit in a field awaiting an alien to make a crop circle – why bother, it’s the unknown, it is unknown and it brings with it danger or a lot of sitting around waiting for something to happen. Sitting down. I hope the team have thought about this; they will be sitting down at water level, when in the dug-out, with knees bent , for many days. There will be a little, roughly hewn, hard bench in which to park our back-sides and then the dug-out will slide slowly away from the bank and we will watch the jungle flow, like a moving picture beside us. No cover, no window to look through, we will be on the equivalent of a motorbike on the M4, smelling the air, feeling the breeze and the full force of nature when the rain pelts us or a storm crashes crazily through the forest. |

green world will flow past us, an enormous mansion that crumbles with primeval finality into the river, then slowly floats downstream beneath the surface before gathering on a bend, a skeletal graveyard of rotting wood and protruding limbs . The Indian spotter is there, at the prow, watching the boat cut through the water, his experienced eye trained to spot the trunks that can upturn us in a split second and his pole will ease us away from the monsters that lie in the murky water below us.

I don’t feel danger. Perhaps I should as I wait for a branch to move and became something that could bite or attack us. I hope I will remain calm; I’ve been there before, I am prepared, but who can tell what will be there this time. For now the river is in my head, as I tick tasks off a list. I am about as immersed in 21st century technology as it’s possible to be and it will all start again tomorrow morning when I awake and add to that growing list! This entry was posted in Speeches on September 6, 2016 by Alison Girdlestone. Many thanks to Craghoppers for their support and proper explorer gear. |

Female Explorers - An Insight - July 2015

|

Undertold stories of brave ladies, who travelled to unknown parts of the world, undeterred by the lack of knowledge of where they were going and the lack of equipment needed to keep them safe, warm, dry and fed have become my passion. That fusion of the lives of others who have enriched our own, the historical context and the wonderful countries they travelled to has led me to gather quite a library of the tales of these women, although many have remained unrecorded.

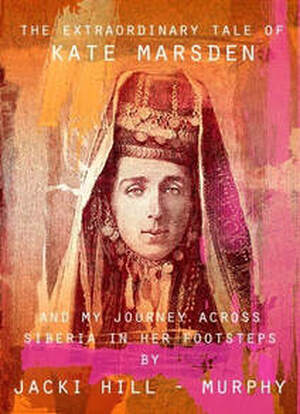

The names of these early women explorers do not have the same familiar ring as those of their male counterparts; Livingstone and Stanley to mention just two. There are many reasons for this, most significant is that many of their voyages occurred in the late 19th century and as the first whispers of New Woman and emancipation were being were heard, the male population were quick to nip in the bud revelations of strong and pioneering women. After following in the footsteps of the first of these great women: Isabela Godin, the first known woman to travel the length of the Amazon River, I found many keen listeners to her tale and my journey. I decided to follow it with another expedition, this time to follow Mary Kingsley’s climb up Mount Cameroon and hard on the heels of this one came Isabela Brooks in the Llanganates in the Andes, Isabella Bird in Ladakh and Kate Marsden in Siberia. I had already thoroughly explored the world of Julia Pardoe in Istanbul and Isabella Eberhardt in Algeria. |

Many of these women’s lives have resonated with my own making my recreation of their journeys more poignant and enlightening. Mary Kingsley and I lived a few yards from each other in Cambridge, at the same age, although 120 years apart, Isabella Bird had a restless spirit which made her hanker to travel, similar to me and Kate Marsden and I suffered physically in the same way from the privations and rigour of traveling through the Siberian taiga.

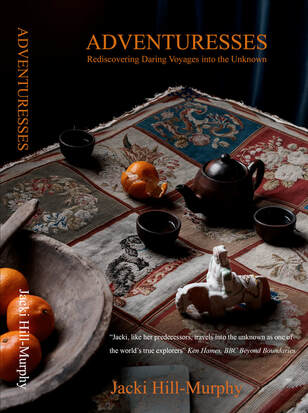

My quest to recreate more brave journeys is not over, the next ones will inevitably uncover the same admirable female qualities. Those of female resilience in extreme conditions, danger and climate and a fair and firm diplomacy in their leadership of others, an innate quality I have observed. These brilliant ladies have helped me to push myself to the limit and allowed my senses to come alive and leave foreign places with a better understanding of the planet and the people who populate it. The last lines of my book (Adventuresses, Rediscovering Daring Voyages into the Unknown) reads: ‘We are all adventuresses who need to travel to be who we are and we are better people for it.” Let’s get talking about the early female explorers and celebrate them with our own intrepid and inspiring journeys into the unknown. Jacki Hill-Murphy This entry was posted in Expeditions on July 10, 2015 by pinkginger. |

Forum Speech 8th June 2015

Good afternoon.

This amazing forum is gathered together for the discussion of practical humanity and it is with great pleasure I want to introduce you to a woman who travelled for a year across Russia, on an extreme humanitarian mission in 1891 and whose story I feel, is an inspiration to us all and holds a special place in the hearts of the people of Yakutia in particular.

Firstly let me tell you why this indomitable Victorian lady has become part of my life.

I am on a project to rescue the names of the early women explorers and pioneers from obscurity. These are women from all over the world who for different reasons, travelled to far away unknown places so that they could document the lives of people who were hitherto unknown in environments that could only be dreamed of; they showed enormous courage and tenacity in their pursuit of knowledge and they wrote some of the first travel books and in doing so, enlightened the world to the plights and pleasures of other societies.

They suffered depravations and faced enormous danger along the way, this lack of safety and backup would be unthinkable to us today and if their lives had been lost, who would have known? Their courage excites and impassions me.

I have been recreating some of these journeys, as closely to the original ones as possible, and have travelled 500 miles in a dug-out canoe along a tributary of the Amazon River in the footsteps of Isabela Godin, the first known woman to travel the length of the Amazon in 1769. I have followed the 1895 journey of Mary Kingsley up Mount Cameroon in West Africa, climbed over the Himalayas of Ladakh to retrace the journey of Isabella Bird in 1889 who did it on a yak and travelled into the Llanganate Mountains of the Andes in Ecuador, one of the wildest and most inhospitable places on earth, in the footsteps of Isabel Brook who died there within three days of setting out to search for the lost Inca gold.

It is important to me to travel the same routes, travel at a similar time of year and although I benefit from better equipment I am mindful of what they took with them and how they dressed, in fact I have walked up a mountain in Africa in a long Victorian dress, in the rain, paying my deepest respects to them as I stepped back into clean and dry trousers afterwards!

Why they did these journeys is an essential criteria to my books and my research has thrown up significant elements in the lives of these women. Mostly they were born in an era that did not facilitate a woman’s curiosity about the world and they were not expected to go and find out. In the 19th century women did not study and have careers, the first female doctors in the UK had to dress as men, the first women colleges did not allow their female students to graduate until the 1920s, if they were born into wealthy families it was expected that they would learn to sew and play an instrument; this was generally the accepted way to attract and marry an eligible bachelor and once married they had no control over their own affairs. Women who were poor had even fewer opportunities. So it is easy to see how society left women feeling emotionally suffocated. These early women explorers broke away from all social convention to do what they did.

Nursing became an option for these women after Florence Nightingale gave it a favourable reputation becoming an icon of Victorian culture, especially in the persona of “The Lady with the Lamp” making rounds of wounded soldiers at night during the Crimean war of the 1850s. She is known for founding the modern nursing profession and her name is internationally familiar to us.

Kate Marsden, was one of the most enigmatic of those early nurses, but there is no evidence that she ever met Florence Nightingale. Kate was born in Edmonton, north London in 1859 and became a nurse when she was 16 and went to work in a London hospital.

Phrases like battle-hardened are used to describe Kate, she was tough and seemed well suited to care for the wounded in the war between Russia and Turkey in 1878. In the play ‘Angel of Mercy’ written in Russian and frequently acted out in Yakutia they depict her falling in love at this time with a soldier there who suffered from leprosy.

There is no evidence that this happened, in fact men or marriage would never feature in her life at all – but some sort of grand epiphany did occur at that time when she encountered more lepers, she said she “saw enough misery to strengthen her resolution.” What had she resolved to do?

By now she was nursing in Constantinople, or Istanbul as we know it today, she saw more lepers and the scene of horror appalled her so much that she started to feverishly pack her bags, “for the swift help of heaven and of men in my mission of relief.”

Leprosy had struck such a chord with her that she had decided to do whatever it would take to find a cure or at least bring relief to the sufferers. She was informed that a herb grew in Siberia that could assist their suffering and that was it, she had made up her mind to find it. In her book she writes:

“I may be called an enthusiast, or a woman who bids high for the world’s applause. I care not what I am called, or what I am thought of, so long as the goal of my ambition be reached, or so long as I may see before I die that the work commenced, though faultily, is on its way to completion.”

Could any of her wartime experiences prepare her for what happened next? She was embarking on the most grueling, equestrian journeys of the late 19th century, in fact I would stick my neck out and say she completed one of the hardest journeys ever undertaken by a woman. The dangers, extreme cold and hardships were so immense that when she published her book ‘On Sledge and Horseback to Outcast Siberian Lepers’ it was received in England as a Victorian gothic horror novel and not as a book about an ambitious humanitarian journey at all.

Now when I put myself in her shoes I ask myself, what do I know about Siberia? My geographical background is very different, for a start we don’t have forests like this that stretch as far as an ocean, full of bogs and bears and if you watch too many TV programmes you would believe that yetis, the size of cars lurk behind the trees and are ready to jump out on you. And there are reindeer like we see on Christmas cards with mossy antlers and bells that are looked after by smiling folk in lovely costumes – What information did she gather 120 years ago? Or did she embark upon the journey without any ideas of the reality?

A google search before I left in 2012 revealed short films on You Tube of snowdrifts inside minibuses and lorries crossing frozen rivers that had traffic lights installed and warnings to keep your engines running all night if necessary and I found an article on Yakutsk, calling it the coldest city in the world that highlighted that if your central heating broke you would surely die… I prepared to leave in September – summer so that my journey in Yakutia would coincide with the time that Kate arrived in the province in 1891, by then she had already been travelling for eight months across Russia through horrifying conditions.

At some point Kate’s mission of mercy turned from looking for the plant that would bring possible relief from leprosy. Incidentally this herb has been identified as Wolf’s plant and I have drunk an infusion made from it, and although I don’t knowingly have leprosy, I can promise you I felt no different after drinking it!

She learnt of the horrific conditions under which Russian lepers were forced to live – this became her new focus.

Before she left, this 31 year old nurse asked for imperial assistance from England’s Queen Victoria, as well as the Empress of Russia, and they gave her their whole hearted support, one wonders if they thought she would ever come back.

The railway had arrived in Russia and Kate travelled on it as far as Zlatoust in the Chelyabinsk region of the southern Urals before transferring to horse-drawn sledges for thousands of miles across the wilds of Siberia. On the early part of the journey she had a female companion but this lady failed to match Kate Marsden’s stamina and had to return to Moscow due to ill health. Kate journeyed on dressed in prodigious quantities of clothing that even the Siberians thought very odd: Jaegar undervests, ‘loose kinds of bodies lined with flannel’, three topcoats, eiderdown ulsters, full-length sheepskin coats, reindeer skin coats, long haired hunting stockings and two sorts of felt boots. All of these clothes left her unable to move and she had to be hoisted into the sleigh by policemen who were there to see her off.

I travelled on the railway to Irkutsk which sits on the southern end of Lake Baikal and from there I desperately tried to find a way to follow her route through small villages on the western side of the lake and catch a cargo boat along the river Lena to Yakutsk – but it wasn’t possible. The villages were mostly gone, I carried with me a 19th century map that I obtained from the Royal Geographical Society but it showed a different Russia from the one we have today and I sadly had to accept that I would have to take the boat up the lake and move away from Kate’s original journey.

The Baikal journey was very beautiful though and while I was gliding over the surface of the deep blue lake staring out at its magical shores, Kate was being jolted and tossed on a sledge at temperatures frequently hitting -50 degrees. She writes in her book: ‘There are gleams of light which you pass on your way that seem to come from tiny hut windows in the forest.’

“Driver” I shouted. “Can’t we stop a minute at one of those huts?”

“Eh, what, madam?”

“Those huts where the lights are on, can’t we rest there? ”

“Lights? They’re wolves eyes!”

When she arrived at a shelter for the night, which was usually just a dirty hut, she would be in a semi-comatose state and need to be dragged from the sledge. She says that on gaining a footing, she felt more like a battered old log of mahogany than a gently nurtured Englishwoman! She describes these primitive hotels saying ‘Have your pocket-handkerchief ready, if you can find it, and place it close to your nostrils the moment the door is opened. The hinges creak; and your first greeting is a gust of hot, fetid air, which almost sends you back; but you remember the cold outside and the cravings of hunger, and so you go in.’

Kate Marsden carried 9,000 New testaments that she gave out along the way, mostly in the prisons, carried 40 pounds of plum pudding, or Christmas pudding as we call it, enough oil wicks to last for 10 years and had frozen lumps of vegetable soup hanging off the edge of the sledges. I carried 3,000 postcards celebrating Kate Marsden which I tried so hard to get rid of along the way that I resorted to leaving little stacks of them under train seats and handing them out to anybody I encountered.

As I neared Yakutia I didn’t have to press my postcards on people anymore – they wanted one. Siberian TV had caught up with me and had been broadcasting snippets of my journey since Tomsk, they knew about Kate and I was soon to start experiencing the love everyone had for her.

It was here in Yakutsk, 5,000 miles form St Petersburg, that the nature of Kate’s extraordinary journey altered course. It was summer by then and the next leg of her journey was on horseback – although she wasn’t a very confident rider. In her words she says: ‘We left Yakutsk for Viluisk June 22nd, 1891, to begin our long journey of 2000 miles on horseback, for the purpose of visiting the lepers living in forests unknown, even to the Russians. Our cavalcade was somewhat curious, consisting of about fifteen men and thirty horses; all those around me were talking in a language which I could not understand.’ She carried a revolver, a whip, and a little travelling bag and had to ride as a man because the Yakutsk horses were so wild that it was impossible for her to ride otherwise; and there were no roads, the horses constantly stumbled on the roots in the forest. For three months she ate black and white dried bread, dried prunes, and drank tea with sugar.

Kate did indeed find the lepers in the forest and documented the horror of their existence in her book. ‘The poor lepers are so looked down upon as the very dregs of the community that even those wishing to befriend them have fallen into the way of thinking that the worst is good enough for them. Some of the people came limping, and some leaning on sticks, to catch the first glimpse of us, their faces and limbs distorted by the dreadful ravages of the disease. One poor creature could only crawl by the help of a stool, and all had the same indescribably hopeless expression of the eyes which indicates the disease. I scrambled off the horse, and went quickly among the little crowd of the lame and the blind. Some were standing, some were kneeling, and some crouching on the ground, and all with eager faces turned toward me. They told me afterward that they believed God had sent me; and, my friends, if you could all have been there, you would no longer wonder at my having devoted body and soul to this work.’

Kate Marsden raised the funds to build a leper colony and it opened a few years after Kate’s visit and this became a turning point in the lives of the lepers. It existed until the 1960s, leprosy became treatable with antibiotics in the 1940s but unfortunately still exists in some parts of the world.

Sadly, circumstances never gave her the opportunity to see her hospital built but she founded the St. Francis Leprosy Guild in London which still exists today. The rest of her life was not a happy one and it seemed to lack the purpose that had driven her to make this remarkable journey, she died in poverty in 1931.

I am going to close by showing you a piece of film. After a 20 hour journey on an unmade road through the forest from Yakutsk I arrived in Vilyuisk and was then whisked off to Sosnovka – the site of the leper colony. What you will see is a welcome within an extraordinary community, and one that had waited 120 years to take place. You see, I think they had waited for her to come and she never did – she couldn’t. I am not a nurse and I didn’t suffer the way she did, but I came in her name and I was given the full honours in her place. It was a deeply humbling and moving experience that I will never forget.

You will laugh because I had to hand my camera to someone to film because I was being filmed myself – and I inadvertently handed it to the Deputy Governor!

What I want to say to you all is that the buildings may have nearly gone and a new hospital with a different purpose has taken its place. But what you are all doing now is the direct result of her, her practical humanity and nerves of steel has left its mark on all of us.

We have found her unmarked and overgrown grave in London and we have cleared it and the people of Vilyuisk have donated a plague. I hope Kate Marsden has found peace. She may look down and smile, in the knowledge that her dreadful journey has brought changes in the world that make life more bearable for the less fortunate. We are all now a part of her project and the work with the needy in the forests here and around the world is the direct result of her.

Thank you.

This entry was posted in Speeches on June 29, 2015 by pinkginger.

Good afternoon.

This amazing forum is gathered together for the discussion of practical humanity and it is with great pleasure I want to introduce you to a woman who travelled for a year across Russia, on an extreme humanitarian mission in 1891 and whose story I feel, is an inspiration to us all and holds a special place in the hearts of the people of Yakutia in particular.

Firstly let me tell you why this indomitable Victorian lady has become part of my life.

I am on a project to rescue the names of the early women explorers and pioneers from obscurity. These are women from all over the world who for different reasons, travelled to far away unknown places so that they could document the lives of people who were hitherto unknown in environments that could only be dreamed of; they showed enormous courage and tenacity in their pursuit of knowledge and they wrote some of the first travel books and in doing so, enlightened the world to the plights and pleasures of other societies.

They suffered depravations and faced enormous danger along the way, this lack of safety and backup would be unthinkable to us today and if their lives had been lost, who would have known? Their courage excites and impassions me.

I have been recreating some of these journeys, as closely to the original ones as possible, and have travelled 500 miles in a dug-out canoe along a tributary of the Amazon River in the footsteps of Isabela Godin, the first known woman to travel the length of the Amazon in 1769. I have followed the 1895 journey of Mary Kingsley up Mount Cameroon in West Africa, climbed over the Himalayas of Ladakh to retrace the journey of Isabella Bird in 1889 who did it on a yak and travelled into the Llanganate Mountains of the Andes in Ecuador, one of the wildest and most inhospitable places on earth, in the footsteps of Isabel Brook who died there within three days of setting out to search for the lost Inca gold.

It is important to me to travel the same routes, travel at a similar time of year and although I benefit from better equipment I am mindful of what they took with them and how they dressed, in fact I have walked up a mountain in Africa in a long Victorian dress, in the rain, paying my deepest respects to them as I stepped back into clean and dry trousers afterwards!

Why they did these journeys is an essential criteria to my books and my research has thrown up significant elements in the lives of these women. Mostly they were born in an era that did not facilitate a woman’s curiosity about the world and they were not expected to go and find out. In the 19th century women did not study and have careers, the first female doctors in the UK had to dress as men, the first women colleges did not allow their female students to graduate until the 1920s, if they were born into wealthy families it was expected that they would learn to sew and play an instrument; this was generally the accepted way to attract and marry an eligible bachelor and once married they had no control over their own affairs. Women who were poor had even fewer opportunities. So it is easy to see how society left women feeling emotionally suffocated. These early women explorers broke away from all social convention to do what they did.

Nursing became an option for these women after Florence Nightingale gave it a favourable reputation becoming an icon of Victorian culture, especially in the persona of “The Lady with the Lamp” making rounds of wounded soldiers at night during the Crimean war of the 1850s. She is known for founding the modern nursing profession and her name is internationally familiar to us.

Kate Marsden, was one of the most enigmatic of those early nurses, but there is no evidence that she ever met Florence Nightingale. Kate was born in Edmonton, north London in 1859 and became a nurse when she was 16 and went to work in a London hospital.

Phrases like battle-hardened are used to describe Kate, she was tough and seemed well suited to care for the wounded in the war between Russia and Turkey in 1878. In the play ‘Angel of Mercy’ written in Russian and frequently acted out in Yakutia they depict her falling in love at this time with a soldier there who suffered from leprosy.

There is no evidence that this happened, in fact men or marriage would never feature in her life at all – but some sort of grand epiphany did occur at that time when she encountered more lepers, she said she “saw enough misery to strengthen her resolution.” What had she resolved to do?

By now she was nursing in Constantinople, or Istanbul as we know it today, she saw more lepers and the scene of horror appalled her so much that she started to feverishly pack her bags, “for the swift help of heaven and of men in my mission of relief.”

Leprosy had struck such a chord with her that she had decided to do whatever it would take to find a cure or at least bring relief to the sufferers. She was informed that a herb grew in Siberia that could assist their suffering and that was it, she had made up her mind to find it. In her book she writes:

“I may be called an enthusiast, or a woman who bids high for the world’s applause. I care not what I am called, or what I am thought of, so long as the goal of my ambition be reached, or so long as I may see before I die that the work commenced, though faultily, is on its way to completion.”

Could any of her wartime experiences prepare her for what happened next? She was embarking on the most grueling, equestrian journeys of the late 19th century, in fact I would stick my neck out and say she completed one of the hardest journeys ever undertaken by a woman. The dangers, extreme cold and hardships were so immense that when she published her book ‘On Sledge and Horseback to Outcast Siberian Lepers’ it was received in England as a Victorian gothic horror novel and not as a book about an ambitious humanitarian journey at all.

Now when I put myself in her shoes I ask myself, what do I know about Siberia? My geographical background is very different, for a start we don’t have forests like this that stretch as far as an ocean, full of bogs and bears and if you watch too many TV programmes you would believe that yetis, the size of cars lurk behind the trees and are ready to jump out on you. And there are reindeer like we see on Christmas cards with mossy antlers and bells that are looked after by smiling folk in lovely costumes – What information did she gather 120 years ago? Or did she embark upon the journey without any ideas of the reality?

A google search before I left in 2012 revealed short films on You Tube of snowdrifts inside minibuses and lorries crossing frozen rivers that had traffic lights installed and warnings to keep your engines running all night if necessary and I found an article on Yakutsk, calling it the coldest city in the world that highlighted that if your central heating broke you would surely die… I prepared to leave in September – summer so that my journey in Yakutia would coincide with the time that Kate arrived in the province in 1891, by then she had already been travelling for eight months across Russia through horrifying conditions.

At some point Kate’s mission of mercy turned from looking for the plant that would bring possible relief from leprosy. Incidentally this herb has been identified as Wolf’s plant and I have drunk an infusion made from it, and although I don’t knowingly have leprosy, I can promise you I felt no different after drinking it!

She learnt of the horrific conditions under which Russian lepers were forced to live – this became her new focus.

Before she left, this 31 year old nurse asked for imperial assistance from England’s Queen Victoria, as well as the Empress of Russia, and they gave her their whole hearted support, one wonders if they thought she would ever come back.

The railway had arrived in Russia and Kate travelled on it as far as Zlatoust in the Chelyabinsk region of the southern Urals before transferring to horse-drawn sledges for thousands of miles across the wilds of Siberia. On the early part of the journey she had a female companion but this lady failed to match Kate Marsden’s stamina and had to return to Moscow due to ill health. Kate journeyed on dressed in prodigious quantities of clothing that even the Siberians thought very odd: Jaegar undervests, ‘loose kinds of bodies lined with flannel’, three topcoats, eiderdown ulsters, full-length sheepskin coats, reindeer skin coats, long haired hunting stockings and two sorts of felt boots. All of these clothes left her unable to move and she had to be hoisted into the sleigh by policemen who were there to see her off.

I travelled on the railway to Irkutsk which sits on the southern end of Lake Baikal and from there I desperately tried to find a way to follow her route through small villages on the western side of the lake and catch a cargo boat along the river Lena to Yakutsk – but it wasn’t possible. The villages were mostly gone, I carried with me a 19th century map that I obtained from the Royal Geographical Society but it showed a different Russia from the one we have today and I sadly had to accept that I would have to take the boat up the lake and move away from Kate’s original journey.

The Baikal journey was very beautiful though and while I was gliding over the surface of the deep blue lake staring out at its magical shores, Kate was being jolted and tossed on a sledge at temperatures frequently hitting -50 degrees. She writes in her book: ‘There are gleams of light which you pass on your way that seem to come from tiny hut windows in the forest.’

“Driver” I shouted. “Can’t we stop a minute at one of those huts?”

“Eh, what, madam?”

“Those huts where the lights are on, can’t we rest there? ”

“Lights? They’re wolves eyes!”

When she arrived at a shelter for the night, which was usually just a dirty hut, she would be in a semi-comatose state and need to be dragged from the sledge. She says that on gaining a footing, she felt more like a battered old log of mahogany than a gently nurtured Englishwoman! She describes these primitive hotels saying ‘Have your pocket-handkerchief ready, if you can find it, and place it close to your nostrils the moment the door is opened. The hinges creak; and your first greeting is a gust of hot, fetid air, which almost sends you back; but you remember the cold outside and the cravings of hunger, and so you go in.’

Kate Marsden carried 9,000 New testaments that she gave out along the way, mostly in the prisons, carried 40 pounds of plum pudding, or Christmas pudding as we call it, enough oil wicks to last for 10 years and had frozen lumps of vegetable soup hanging off the edge of the sledges. I carried 3,000 postcards celebrating Kate Marsden which I tried so hard to get rid of along the way that I resorted to leaving little stacks of them under train seats and handing them out to anybody I encountered.

As I neared Yakutia I didn’t have to press my postcards on people anymore – they wanted one. Siberian TV had caught up with me and had been broadcasting snippets of my journey since Tomsk, they knew about Kate and I was soon to start experiencing the love everyone had for her.

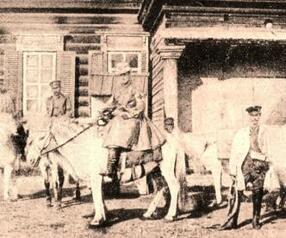

It was here in Yakutsk, 5,000 miles form St Petersburg, that the nature of Kate’s extraordinary journey altered course. It was summer by then and the next leg of her journey was on horseback – although she wasn’t a very confident rider. In her words she says: ‘We left Yakutsk for Viluisk June 22nd, 1891, to begin our long journey of 2000 miles on horseback, for the purpose of visiting the lepers living in forests unknown, even to the Russians. Our cavalcade was somewhat curious, consisting of about fifteen men and thirty horses; all those around me were talking in a language which I could not understand.’ She carried a revolver, a whip, and a little travelling bag and had to ride as a man because the Yakutsk horses were so wild that it was impossible for her to ride otherwise; and there were no roads, the horses constantly stumbled on the roots in the forest. For three months she ate black and white dried bread, dried prunes, and drank tea with sugar.

Kate did indeed find the lepers in the forest and documented the horror of their existence in her book. ‘The poor lepers are so looked down upon as the very dregs of the community that even those wishing to befriend them have fallen into the way of thinking that the worst is good enough for them. Some of the people came limping, and some leaning on sticks, to catch the first glimpse of us, their faces and limbs distorted by the dreadful ravages of the disease. One poor creature could only crawl by the help of a stool, and all had the same indescribably hopeless expression of the eyes which indicates the disease. I scrambled off the horse, and went quickly among the little crowd of the lame and the blind. Some were standing, some were kneeling, and some crouching on the ground, and all with eager faces turned toward me. They told me afterward that they believed God had sent me; and, my friends, if you could all have been there, you would no longer wonder at my having devoted body and soul to this work.’

Kate Marsden raised the funds to build a leper colony and it opened a few years after Kate’s visit and this became a turning point in the lives of the lepers. It existed until the 1960s, leprosy became treatable with antibiotics in the 1940s but unfortunately still exists in some parts of the world.

Sadly, circumstances never gave her the opportunity to see her hospital built but she founded the St. Francis Leprosy Guild in London which still exists today. The rest of her life was not a happy one and it seemed to lack the purpose that had driven her to make this remarkable journey, she died in poverty in 1931.

I am going to close by showing you a piece of film. After a 20 hour journey on an unmade road through the forest from Yakutsk I arrived in Vilyuisk and was then whisked off to Sosnovka – the site of the leper colony. What you will see is a welcome within an extraordinary community, and one that had waited 120 years to take place. You see, I think they had waited for her to come and she never did – she couldn’t. I am not a nurse and I didn’t suffer the way she did, but I came in her name and I was given the full honours in her place. It was a deeply humbling and moving experience that I will never forget.

You will laugh because I had to hand my camera to someone to film because I was being filmed myself – and I inadvertently handed it to the Deputy Governor!

What I want to say to you all is that the buildings may have nearly gone and a new hospital with a different purpose has taken its place. But what you are all doing now is the direct result of her, her practical humanity and nerves of steel has left its mark on all of us.

We have found her unmarked and overgrown grave in London and we have cleared it and the people of Vilyuisk have donated a plague. I hope Kate Marsden has found peace. She may look down and smile, in the knowledge that her dreadful journey has brought changes in the world that make life more bearable for the less fortunate. We are all now a part of her project and the work with the needy in the forests here and around the world is the direct result of her.

Thank you.

This entry was posted in Speeches on June 29, 2015 by pinkginger.

WHITE NIGHTS IN THE DARK FOREST

|

Twenty four hours of daylight can play havoc with your body clock, particularly one that is already jet lagged from crossing numerous Siberian time zones en route from the UK. I closed my eyes and willed myself to sleep while a searchlight of sun shone into my face through a gossamer-thin curtain.

It would be a week before I saw the sun set again. A white night in June never gets dark at high latitudes and Yakutsk in Sakha Province is located about 450 kilometers south of the Arctic Circle. Yakutsk is a city of many extremes; it is the coldest city on earth built alongside the River Lena. The permafrost ground creates an architect’s head ache and concrete piles hold up the buildings which are laced with crudely lagged waste and water pipes that can’t be dug under the ground. If it’s not enough for the Yakuts to scuttle around for eight months with temperatures as low as -60°C, they also do that in the dark, as December daylight is from 11.00 am till 3.30 pm. As I tried to sleep in the night sunshine I wondered whether Yakuts people, deprived of sun and light for so much of the year sunbathed at midnight to compensate. I’d seen them with shopping bags on the ride from the airport at 3am and I marvelled at the human’s ability to adapt to such difficult surroundings. |

I love these people and when my clock told me it was morning I sprang out of bed in that bright room, ready to head off on a 600 kilometer car journey through the forest, that’s the equivalent of driving from Brighton to Edinburgh in Great Britain, on an unmade road for my second visit to Vilyuisk. Look at a map and you are reminded that an ocean of wild, inhospitable forest surrounds Yakutsk that is as big as America and driving through it is endless. Vilyuisk is a mere pin prick. It’s an island village of 12,000 people in this ocean of trees whose lives are geared to the rhythm of nature and the seasons. They are the woodlanders and the horse breeders who now boast a successful teacher training college. They lead cultured and respectable lives in their wooden houses, driving their cars over mud tracks and there are women’s groups who sew beautiful flowery long dresses who look forward to a guest visiting their town to dress up and sing for…

Remarkably, I was the first visitor since I came two years earlier. I was in for a treat. The town had been preparing for my visit and I was about to receive the full Vilyuisk treatment … Next: The Museum with no Visitors Chineke Folk Slivers, Pebbles and Dive – the games made at the Yakutsk Disabled Unit The Beauty of the Lena Pillars Portraits of the People of Yakutsk Traditional Costumes and Rituals of the Yakuts This entry was posted in Expeditions on June 29, 2015 by pinkginger. |

I Wouldn’t Go There if I Were You

|

Personally, I couldn’t even begin to consider putting myself in Mary Kingsley’s shoes when I began to plan to follow in her footsteps of one of her epic journeys. Even now, I can’t account for how she learnt to accommodate herself to sleeping in the rain on mountainsides, spending days and nights floating in a roughly made boat on a tropical river, putting up with wearing damp, smelly and dirty clothes, intense heat and insects and other wildlife and the eyes of men incessantly staring at her as she travelled.

How did she find the negotiating skills to hire and fire hopeless porters and guides and handle the reliable ones? Where, in her sequestered teens and twenties did she learn the necessary tenacity when she booked her first passage for Africa a year after that brief Canaries reconnaissance? She showed such courage and had strong morals and stuck to them. In reading about her life, it was the sheer moral greatness and the sense of underlying purpose, that was borne in on me; and inevitably she became an inspiration to me, opening my heart to a pulse of adventure, far beyond my own upbringing and situation, as I sought to understand her. ‘Hints to Lady Travellers‘ of 1889 with its offerings of practical advice and safety tips with headings of ‘Cabs’, ‘Cushions’, ‘Cycling Tours’ and ‘Dress-hampers’. Something that Mary Kingsley would have known – without needing to be told was that: ‘From the first moment when the traveller sets foot upon foreign soil, and sees the strange surroundings, the quaint dresses, and curious customs of the natives, enhanced by the clear air and brilliant sunshine, so different from the softened atmosphere at home, she experiences all the effect of having entered into a new life.’

For a start, she was hardly likely to be concerned that: ‘Care should be taken in selecting a deck chair not to get one which is too light, otherwise your enjoyable after-dinner nap on deck may be abruptly terminated by a sudden lurch of the vessel, and you may find yourself overturned, chair and all, and sent flying to the other side of the ship in a manner more sudden than graceful.’ The vessels she sailed on were never going to offer that level of luxury. On the eve of her departure to Africa, kind friends thrust into her hands a new ‘French book of phrases in common use in Dahomey’. Less naive than Lillias’s advice, it oozes imperialism. The opening sentence of the book was ‘Help, I am drowning’, is followed by ‘Get up, you lazy scamps!’ The question ‘Why has not this man been buried?’ is answered by ‘It is fetish that has killed him, and he must lie here exposed with nothing on him until only the bones remain.’ It is hard to guess whether Mary Kingsley would have responded with a smile, or with outrage, to the well-intended gift. It was on Mary’s second trip to West Africa, in 1894, that she took an interest in Mount Cameroon. She was sailing on The Royal Mail steamer ‘The Batanga’ again and, as on her first trip, she was the guest of Captain Murray. Their course took them from the Canaries by way of Sierra Leone to Gabon, and Murray was careful to draw her attention to West Africa’s highest peak. Emerging from, and disappearing back into, its tropical mist it must have looked to her like no other mountain. At once a fire of excitement was kindled in Mary Kingsley; up to that moment she had seen her destiny as somehow related to her father’s scientific work, earning the applause of those back at home, but suddenly this whole extraordinary business of being a white woman where white women didn’t go needed no justification. That mountain, tantalisingly glimpsed from the sea, gave her a strong urge to climb it. Though never a feminist, she was showing a desire to shed the late Victorian obligation that women should not be pioneers, it was a patronising attitude that her journey to Africa was more acceptable as she would carry on the scientific work that her father started. Mary’s decision to climb a mountain, that certainly offered no fish to collect, was a brave move. |

so far as we know, had been before.

She was experiencing some of the remotest parts of Gabon and the French Congo where the river was often interrupted by rapids and inhabited by all three species of the African crocodile. Beyond the reach of her canoe, the banks were cloaked with rainforest and its attendant raucous wildlife; and conscious perhaps of, her father’s anthropological notes, Mary made a point of visiting, and recording her impressions of the Fang tribe with their reputation for fierceness and cannibalism. Compared to the cooking-pot, the modern female traveller has little to fear: Women can expect unwanted attention from men, marriage proposals and, in share-taxis, the occasional groping, as I discovered from Lonely Planet when researching visiting Gabon. Mary Kingsley, probably the first white woman to visit upper Gabon, made up her own rules as she went along, used her Victorian upbringing and attitudes to shield herself from harm and unwanted attention, was bossy and forceful when she needed to be – and prodded a few people (and hippos and crocodiles) with her umbrella. Nothing that she saw there was so bad as to make her want to go home. She obviously fell in love with the country; the feeling of foreboding with which she had left Liverpool Docks on her first trip to Africa, on the S.S. Lagos, in 1893, was quickly dispelled, allowing her to write that: ‘The charm of West Africa is a painful one: it gives you pleasure when you are out there, but when you are back here it gives you pain by calling you. It sends up before your eyes a vision of a wall of dancing white, rainbow-gemmed surf playing on a shore of yellow sand before an audience of stately coco palms; or of a great mangrove-watered bronze river; or of a vast aisle in some forest cathedral: and you hear, nearer to you than the voices of the people round, nearer than the roar of the city traffic, the sound of the surf that is breaking on the shore down there, and the sound of the wind talking on the hard palm leaves and the thump of the natives’ tom-toms; or the cry of the parrots passing over the mangrove swamps in the evening time; or the sweet, long, mellow whistle of the plantain warblers calling up the dawn; and everything that is round you grows poor and thin in the face of the vision, and you want to go back to the Coast that is calling you, saying, as the African says to the departing soul of his dying friend, “Come back, come back, this is your home.’ Returning to the coast after four months in Gabon, seemingly without ensuing anxiety after her encounters with wild life and the Fan tribe, she left on the Niger commanded by Captain Davies. The regret of leaving the charms of the French Congo, she noted were compensated by being on such a comfortable ship. Relaxing on deck, trying no doubt to assimilate the extraordinary sights and encounters that she had experienced, once again her eyes fixed on ‘her temptation’; Mungo mah Lobeh, the Throne of Thunder as she had learnt to call the magnificent Mount Cameroon. By the time it was my turn to negotiate it, the name had side-slipped to Mongo ma Ndemi, or The Mountain of Greatness. Both Mary’s and my expeditions were bound to be as much about the weather and the eclectic mix of characters both accompanying, and encountered by, us, as the climb itself. My aim was for a team comprising like minded people and harmony; but in my early days of expedition-planning I had come to realise that my original criteria for selection were too obvious, too simplistic, namely, 1, take anybody who wants to go because I am offering an experience to be shared, 2, locate a skill that they can use to benefit the expedition, 3, we’ll all get on because we are adults and it’s not a school trip. After that, with each step up the mountain, each hurdle crossed, each evening fireside chat a bond would be made to last all of our lives, meeting up for regular reunions to watch film footage and swap stories and photographs. Unfortunately, it didn’t work out quite as I had hoped and I am using its mishaps to cast light on the difficulties that Mary would experience. This entry was posted in Expeditions, Mary Kingsley on December 12, 2014 by Alison Girdlestone. |

For information on how to purchase Adventuresses please click here

Crinolines in the Jungle

|

Once again I tried to put myself in Isabela’s embroidered slippers, and imagine her mixture of abject discomfort and apprehensiveness at every unfamiliar sound or movement of the alien forest, from the sudden fall of a tree to the cry of the bellbird and the bark of the howler monkey. Pinch yourself Jacki,

|

|

in the sealed safety of your dry cab; at least you have the assurance of arrival at the end of the ride! I noticed my team mates had gone a bit quiet and guessed that Mary in particular was pondering the recklessness of the expedition leader in transferring us all to the Bobonaza, in a dugout canoe of all things, in weather like this.

My own excitement though, increased, as we reached Canelos. The rain had reduced to a drizzle and a thick white mist hung over the forested hillsides. Women and children stared out at the quartet of pale-skinned women from their unglazed windows of bright pink-painted shacks with silver corrugated roofs; we were an unusual sight, this was not a tourist route by any means and more children, chickens, dogs and old men came out and stood at the side of the track under pole barn roofs and verandahs and watched our yellow taxis drive by. I was aware of the Bobonaza running close by and glimpses through the trees had shown a wild, brown river getting wider and faster and then we crossed a short stretch of metal bridge, turned and at the bottom of an incline the road simply disappeared into the river’s chocolate eddies, and there, ahead of us, moored parallel to the bank, was our 40’ dug out canoe – I shivered with excitement. Jean Godin himself takes up their story in an eloquent letter to Monsieur De la Condamine, Member of the Academy of Sciences at Paris, and leader of the expedition that had taken him to South America, describing Don Pedro’s progress and Isabela’s party’s arrival: ‘….. she reached Canelos, the spot at which they were to embark, situated on the little river Bobonaza, which empties itself into the Pastaza, and then into the Amazon. M. de Grandmaison, had gone on ahead by a month, found the small town of Canelos, and immediately set off on his journey, preparing everything necessary for his daughter’s journey up the river at each stage of her way. As he knew that she was going to be accompanied by her brothers, her black servant and three female maids, he proceeded on to the Portuguese missions. In the interval, however, between his journey and the arrival of my wife, the small pox, a European disease, more fatal to the Americans in this part than the plague, had caused the village of Canelos to be utterly abandoned. They had seen those first attacked by this illness die, and so ran away and scattered in the woods, to remote huts. |

such a terrible turn of events was to be done ? Even if my wife had been able to return she didn’t want to, she really wanted to reach the waiting ship, because she wanted to join me, her husband from whom she had been parted for twenty years. This was the powerful incentive to make her, in the peculiar circumstances in which she was placed, brave even greater obstacles.’

It was almost with guilt that I stood there staring at my beautiful dug-out canoe, complete with the best guarantee of progress – its outboard motor. The knowledge that Mary and Julia and I were the first females since 1769 to follow in Isabella’s pioneering tracks makes me bold to record our own 21st century reactions. Everything was in place; the rain had stopped, the sun had come out and it suddenly seemed that we had it so easy. Within minutes, boxes of fruit and vegetables securely stowed in waterproof bags and large sealed plastic containers of bread, biscuits and juice were being handed along a human chain to two smiling Indians who stood, bare legged, in the swirling shallows of the Bobonaza, neatly fitting the mountain of baggage into the small hold of the canoe. Next went our kit, the sleeping mats, tents, camera bags and bottles and bottles of water and cans of fuel. More heads joined the gaggle of onlookers and an Indian woman with a crying baby sat in the grass observing all this going on intently, disregarding the child’s ever increasing demands and louder screams. These two, it transpired, were to be our extra passengers. We really had – I thought – hired the jungle bus, the crucial means of communication between the remote villages on the river. While I marvelled at the competence of the preparations, my two companions further up the bank were aware only of the bullet speed of the river: a fallen branch passed in a split second. “It’s pretty, pretty wild, isn’t it – and this canoe doesn’t look big enough for seven or eight people.” exclaimed Julia. “They are cutting us some balsa wood from that tree up there for us to hold for buoyancy…” I replied, concealing my anxiety that they might be wanting to back out. Mary cut in: “I am apprehensive about going on that river, it looks really fast flowing, I’m a bit worried to be honest, the water level is right up.” |

|

The fingers of both my hands were tightly crossed inside my trouser pockets. I said nothing; but the adventurer in me was screaming “Let’s just go!” I was so desperate to get on that river. Somehow, the message got through: like good sports they clambered into the canoe, perched themselves on the primitive thwarts and followed me in hoinking off their wellies, just in case we capsized.

As we pushed off, I made a head-count: there were at least a dozen adults aboard. Even so, the canoe rode the fast flowing river water well, and with the outboard’s help we were assured that we would be at our first stop, Sarayaku, within hours. Even the baby seemed pacified by the motion of the boat and lay fast asleep on her mother’s shoulder. Our smooth departure was in sharp contrast to that of Isabela’s party. Jean Godin, in his letter to La Condamine explained how the smallpox reached Canelos first. The moment that her mountain Indian bearers realised that contagion had struck, they melted away the way they had come. The party searched the burnt ruins of the abandoned village, finding just two forest Indians who had escaped infection: as for the boats, they were gone, whether used for escape or set on fire with the rest of the village to drive out the evil spirits. Questioned, the men they found said they had the skills to make and man a largish canoe; it would take two weeks, and the journey down river to Andoas roughly twelve days. The men were paid in advance, rousing the three French strangers to furious objection. They urged Isabela to turn back, but she overruled them; however the reduction of three boats to one, and a sizable crew to just two, meant that any excessive weight, and all her family treasures, had to be abandoned at Canelos – the price of allowing these feckless Frenchmen to travel with them. Not only had the trio proved thoroughly disruptive, but it became increasingly apparent that they shared not a scrap of medical knowledge between them. Counting adults and children, thirteen embarked that first day. The Indians made good progress at the paddles, and that night they found a dry sand bank to pull up on, and made a good fire for their passengers. This was probably the one survival skill in which the Indians surpassed Isabela’s party, and it proved to be the only one: not one of the thirteen knew how to swim. The best they could do when danger threatened was to pray to God, or gods, to save them, and they were going to need all their praying-muscles from day three onwards. Our own first day on the fast-flowing and swollen Bobonaza went smoothly, too; we arrived at Sarayaku late in the afternoon and we were made immediately welcome. The inhabitants of Sarayaku’s ancient ancestral territory lying in Ecuador’s remote Amazon tropical rainforest are Kichwan and number around 1,200. But this is no ordinary indigenous region: Sarayaku is where the people rose up accusing the Argentine oil company CGC of ethnocide after the industry ruined their means of subsistence, caused widespread ecological and spiritual damage and undermined the social balance of the community. |

In the early 2000s the oil company occupied part of the Sarayaku lands with the encouragement of the Ecuadorian state government in order to prospect for oil using seismic surveying methods; there had been no prior consultation with the Sarayaku people. Realising its mistake, the government sent federal soldiers to Sarayaku, in order to stop indigenous resistance and closed the Bobonaza River as a traffic artery.

The Sarayaku people responded with well-orchestrated protests at a national and international level and forced CGC to withdraw from the project; but in the face of the state authorities’ failure to apologise, provide compensation or pastoral redress, or make commitments about preventing similar abuses, the people of Sarayaku proclaimed their region a self-governed territory called ‘Tayjasaruta’ or ‘Autonomous Territory of the Original Kichwa Nation of Sarayaku’. The state economy of Ecuador is dependent on constant income from crude oil export to pay off the national debt, and so, after exhausting all domestic legal avenues for redress and a guarantee of non-repetition, Sarayaku decided to take their case to the Inter-American Court of Human Rights. In July 2012 the judges ruled in favour of the Sarayaku people. In 2012, the film titled ‘Children of the Jaguar’, co-produced by Amnesty International and the Kichwa de Sarayaku Indigenous community,and documenting the legal struggle, was released at film festivals. ‘Children of the Jaguar’ was awarded “Best Documentary” by the All Roads Film Project of the National Geographic Society. The story was of absorbing interest to me: years before, when my son was still a baby and I could only dream of visiting the Amazon and accepting the hospitality of an indigenous community, alarms were raised about the exploitation of the Kayapo territory of Amazonian Brazil for logging. Incensed, I faxed off my design for a tee shirt to the Rainforest Foundation, and the fact that that shirt seemed to be everywhere for one whole hot summer in the nineties helped in a small way to throw a protective cordon round some 27,000 square kilometres of Kayapo rainforest and set up an alarm system to warn indigenous groups of the approach of illegal loggers. My curiosity continued to grow; and now here I was, helping to unload a canoe in the advancing darkness, against a backdrop of alien sounds and indigenous Kichwa faces. In the morning, with my feet still in the sleeping bag, I pulled back the flap of the tent, and peeped out into a living enactment of all the documentaries I’d ever watched on the Amazon basin since childhood. Our covered camp stood among between a collection of skilfully thatched buildings comprising a primary school and the compound of Jose Gualinga, the village chief. His sons Heraldo and Alberto and the striking Ingaro were among our boatmen and guides, Ingaro; an incredibly handsome man, was already sitting at a picnic bench waiting for us as we emerged on that first morning to help us prepare our western breakfast, as he would on subsequent days. |

|

Our covered camp stood among between a collection of skilfully thatched buildings comprising a primary school and the compound of Jose Gualinga, the village chief. His sons Heraldo and Alberto and the striking Ingaro were among our boatmen and guides, Ingaro; an incredibly handsome man, was already sitting at a picnic bench waiting for us as we emerged on that first morning to help us prepare our western breakfast, as he would on subsequent days.

As the early mist was burnt off to reveal the blue sky of another scorching day, we talked with him and his brothers, and Luis, and the other men and women who wandered over. The scene repeated itself in the evening when he played his guitar and sang soulful, Kichwa songs by candlelight. Ennchanting children with jet black hair cut into little bobs played around us and sat on our knees, chickens scratched around under our table and instant translations flew about in our three languages (Eva had two of them) while we absorbed the spirited banter about Sarayaku’s new ecotourist economy and the community’s ongoing troubles with the Quito government. The village spreads out over opposing banks of the river; joined by a high rope and wood suspension bridge which we were coaxed over by Ingaro on the first afternoon to attend a La Minga, the community farming event. It swayed precariously under us, as we picked our way over the missing planks. There were dogs flopped everywhere; when I asked Ingaro why there should be so many dogs lolling exhausted in the heat, he replied that they were to ward off evil spirits and create good energy. Beyond open-walled classrooms where adults were being taught Spanish, we crossed plank bridges to a slope where the land was being cleared for manioc planting; the young women taking part had suspended their babies from branches in large squares of calico, their faces carefully protected from the insects, just as if newly delivered to the village by storks. Such cooperative work among family and friends is rewarded by a feast; we were invited, and I watched as the landholder’s wife dished out a steady stream of chicha beer, which, I was intrigued to learn, is made from manioc, masticated by the women and spat out to aid fermentation; the night’s fare was boiled manioc and river fish which she had stayed up all night to smoke over a wood fire. I took my seat on a low bench next to a tiny girl with a baby monkey clutched to her tee shirt, and surveyed the living arrangements of this rainforest house: the two floors were open to the breezes; there was no evidence of mosquito nets, or privacy. I looked across at Julia, and she thought and replied – for all three of us – “If you live here you live at the pace of nature, at home I run around all day, in and out of my car and clutching my phone, but here life is so calm.” |

Ingaro would take over from his father as village shaman one day; his knowledge of the fruits of the forest and their properties and nutritional values was immense. With Isabela’s starvation in the forest in mind, I made notes of all he said and did. He cut us some bitter fruits for us to taste, then chopped out the heart of a palm which he said she would have been able to find easily. It was sweet and satisfying even in a Western mouth and indeed I remember having eaten some in a salad in Quito.

The next morning we shook insects of alien dimensions from our wet clothes drying on the line while Ingaro coaxed a tarantula from the bowl of the little white-washed privy that stood proud in the midst of some homely huts – a matter of moments before Julia felt the call to use it. In the late afternoon it was time for Julia, Mary, Eva and I to cool down in the washing pond; we headed off armed with shampoo, soap and towels – hoping that Ingaro wouldn’t follow us and that there wouldn’t be a repeat of yesterday’s discovery of a baby cayman in its clear water. This had been eaten by the locals. We splashed about under the trees, laughing as our precious soap slipped to freedom out of our hands and alarming one another with the tales of vampire bats from the forest, stalking on their hind legs up a person’s thighs to choose a tasty bite. It got more girly as we turned to the secret of Ingaro’s thick, glossy-black pony tail, and the particular grass he had shown us that morning in the forest, from which he made a special infusion to anoint it with, he had called it Gillette grass because it was razor sharp. We all admitted – his hair was in great condition. It was too hot to get out of the cool, refreshing water; only when long shadows began falling across it did we finally grab our towels and step out onto the grass. As we did so, two figures walked towards us, Ingaro and his brother Alberto. We dried off while the two Indians slipped into the pond. I’d like to say it was their amiable and unselfconscious physiques with strong arms and legs that reflected the genes of hunter gatherer that my eyes were drawn to, but something else had caught my gaze, the bottle of Head and Shoulders shampoo Ingaro was trying to hide behind his back! This entry was posted in Expeditions, Isabela Godin on December 12, 2014 by Alison Girdlestone. For information on how to purchase Adventuresses please click here |

The Lonely Grave - A Lonely London Grave gets some Siberian Love

by Jacki Hill-Murphy

|

On the 82nd Anniversary of the Victorian nurse and explorer Kate Marsdenʼs death, her unmarked and overgrown grave has been found and an interesting ceremony has taken place to mark her life…

Tucked away on the far edge of Hillingdon cemetery near Uxbridge, an unmarked grave has laid, unvisited, for over 80 years – until 2014. It lies beneath a canopy of straggly May blossom and beside the plastic detritus of a hedge bordering a housing estate and sinking Victorian graves that look like they have been washed up in a storm. This is the final resting place of Kate Marsden (1859 – 1931) to some a hero, tough experienced nurse, fund raiser, who had made a remarkable journey across Siberia in 1891 and established the first leper colony in Russia. To others though she was a fraudster, a deceiver and totally immoral and she was hounded unmercifully until she died, penniless and alone, in a Wandsworth mental institution at 72. Undaunted by the criticism made against her I set off last summer to recreate 4,000 miles of her grueling journey, which she undertook in 1891 by sledge, cart, cargo ship and on horseback, across Siberia, most of it in sub-zero conditions. Kate had become obsessed with the idea that she could mastermind some sort of cure or relief for the lepers she had been encountering whilst nursing the wounded men of the war between Russia and Turkey in 1878 and was told there was a herb in Eastern Siberia that may do that; it seemed to have been the purpose she was looking for in her life. She left after seeking out imperial assistance from Englandʼs Queen Victoria and Maria Feodorovna, Empress of Russia. The journey for her was horrendous and documented in her book ʻOn Sledge and Horseback to Outcast Siberian Lepersʼ, although frustratingly for me, trying to revisit it, there are huge chunks of the journey that she doesnʼt comment on, for example, over 2,000 miles on a crude, insect infested cargo boat on the great River Lena which only receives a paragraphʼs mention. These omissions, plus a title more synonymous with a Gothic horror novel, became a portal in which skepticism would be fostered in an era where women were not applauded for any fantastically dangerous and courageous adventure. While in Russia her focus shifted when she heard about the horrific conditions under which Russian lepers were forced to live and she set off from Yakutsk, on horseback, on a two thousand mile journey to visit lepers in the forests around Vilyuisk to gather information and see for herself the terrible conditions in which they were forced to live. By doing this she inadvertently completed one of the most difficult equestrian journeys of the late 19th century. The money she raised afterwards built a leper colony for these wretched people. I can vouch that she made that journey. The final leg of my overland journey to follow in her footsteps in August 2013 was a 20 hour, 400 mile, minibus journey on unmade roads through the Siberian forest from Yakutsk to Vilyuisk. After meeting the Mayor I was taken to Sosnovka, eight miles away, where the leper colony was built, which opened in December 1892 and carried on its great work through |

the Bolshevik revolution and the civil war before closing in the 1960s. There is now a hospital for dementia patients on the site adjacent to the remains of the collapsing wooden leprasorium.

The raptuous welcome from the villagers of Sosnovka completely took me by surprise, they had come out to greet me in costumes representing the history and tradition of the region, including many in nurseʼs uniforms dating back to the 1890s; there was even a Kate Marsden herself in her little grey suit and hat. The Director of the hospital, Kleopatra, proudly showed me and my travelling companion Rebecca, who was incidentally the first Australian to ever visit Vilyuisk and Sosnovka, the little museum dedicated to Kate Marsden and this costumed community followed us in a throng on a guided tour of the site. It is not possible to feel more love for a deceased person than those people showed for Kate Marsden, after a succession of Siberian tea parties and mareʼs-milk sipping ceremonies, where I had a horse-hair switch swished around me and speeches were made I was led to an empty plinth on a patch of grass. Kleopatra told me that this was waiting for Kateʼs statue; perhaps soon they would have the funds to erect one. Kate Marsden never returned to see her hospital built with the funds that she raised; she never returned to Siberia. She became one of the first women to be elected a Fellow of the Royal Geographical Society and founded the St. Francis Leprosy Guild in London but scandal continued to dog her for the rest of her life and there were campaigns to discredit her in England, Russia and New Zealand. Charges against her included embezzlement of the funds that sheʼd raised to build the hospital, deception by orchestrating falling out of a linen cupboard in a hospital in Wellington in New Zealand, where she was a matron, shortly after buying two life insurance policies. However, most unforgivable were the allegations of lesbianism, this at a time when Oscar Wilde was on trial. They may have been unproved but they were enough to destroy her reputation. On that Saturday in March a motley crew of singing and harp-playing Siberians and British devotees gathered around the sad sight of Miss Marsdenʼs grave, barely visible beneath its blanket of brambles and weeds in a West London Cemetery. It had been found by the present day Kate Marsden, an indomitable figure to the Victorian Kate Marsdenʼs cause. Elena Kychkina, the sister of my translator in Vilyuisk happened to be in London and she also happened to have Kuprian Mikhailov an actor of the Sakha National Drama Theatre with her who just happened to have had a dream to bring his shamanʼs outfit with him and they hung their rag streamers, read out a eulogy, gave Russian pancake offerings, the shaman beat his drum and shook his long hair and we laid our offerings on the newly cleared grave. They told me afterwards, ʻthere was some mystic in the air as though the ceremony was being guided by bright powersʼ. Kate Marsden would have loved it. This entry was posted in Expeditions on November 23, 2013 by pinkginger. |